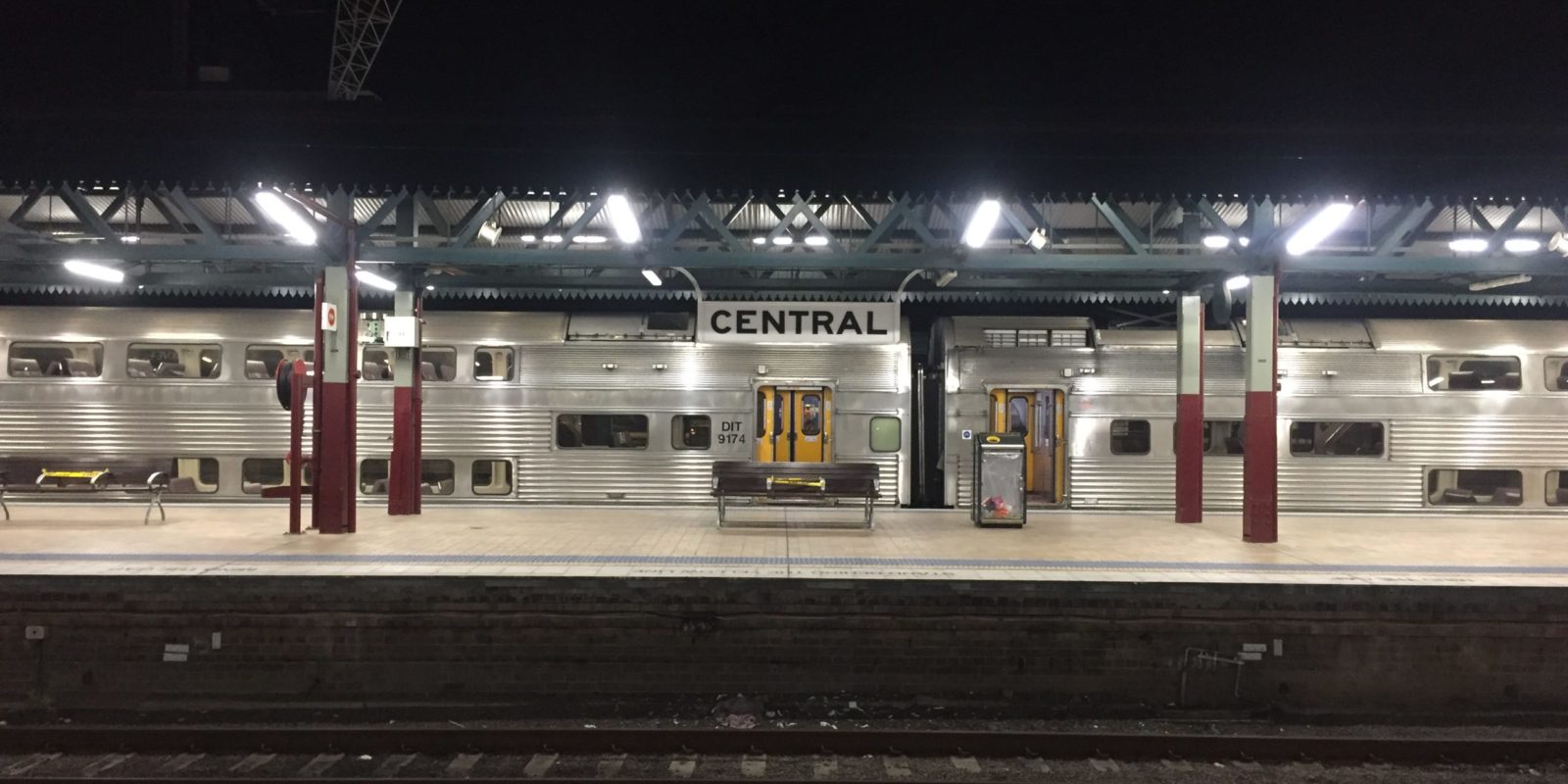

2020’s winter has been quieter than usual in Australia. At 7 p.m., Central Station’s busy hour, its splendid and magnificent grand concourse is filled with cold air and only a handful of people. With the early fall of the winter night, it almost looks as if it’s the wee hours. The normally bustling George Street has gone, Chinatown is empty, Apple’s iconic giant glass walls no longer reflect the throngs of people, the winter of 2020 is particularly hard for Chinese students in Australia.

It all started with the pandemic…

The year 2020 is off to a bad start for many Chinese students studying in Australia. In February 2020, an entirely new infectious and transmitted disease broke out in China and rapidly spread around the world —— COVID-19. From 11 January to 30 January, in just 20 days, China has gone through the first death caused by coronavirus, the lockdown of Wuhan, and later the whole Hubei Province, and WHO’s announcement of a global public-health emergency. It was also the time of the Chinese Spring Festival when numbers of Chinese students went back to their hometown to celebrate the Chinese New Year. Many students were thus being stranded in Hubei province. Under the threat of COVID-19, the United States was the first country to shut its door to China. Australia was a close second, announced a ban on flights from China on 1st February. By the time, it was less than a month away from the start of Australia’s new semester. Students stranded in China began to worry about their trip back to Australia.

“I had to go to a third country in order to get back to Australia and I was worried sick. I was in Thailand for 14 days before flying to Sydney,” said Sihan Wang, who is studying for a master’s degree at the University of Sydney. Despite her mother has a house in Thailand, the trip still cost her about ¥30,000.

“Flights kept getting canceled, and I had no idea which flight was available. Everyone was holding about several tickets at once. Tickets were extraordinarily expensive. Some of them could not be refunded and were just wasted,” She added.

“I flew from Phuket Island and it overall cost me about ¥35,000,” said Yanyun Zhang. She is one of the lucky ones who returned to Australia successfully during this outbreak.

Hui Xiang, another graduate student at the University of Sydney however, was not so lucky. During her 14 days in Thailand, COVID-19 outbroke in Australia. After a serious struggle, she decided to go back to China and defer the semester. During this process, she wasted more than ¥20,000.

These Chinese students spent huge amounts of money and time just to be able to get back to school normally. Unfortunately, most of them have not received any compensation for their loss.

After the University of Sydney published its financial assistance policies for international students, Yanyun immediately made an application. However, the result was disappointing.

“I didn’t get any email for notification. When I found out I have to upload more information, it was already the second day after the deadline. I emailed to ask why I hadn’t received any notification, they didn’t reply to my email at all,” Yanyun said.

“The requirements for the application was confusing. Initially, there was no requirement for a bank statement and there were people receiving compensation without uploading this information.

“I heard that a lot of students didn’t receive any informing email, just like me,” she added.

In the end, Yanyun received no compensation at all, and she wasn’t the only one. According to SUPRA, more than 7,000 students applied for financial assistance, but only about 1,000 received compensation.

The difficulties then escalated, Chinese students are in a serious dilemma

With the further spreading of the pandemic, many Chinese students have gradually found that economic pressure might not be the only difficulty they have to face.

The COVID-19 outbreak has led to a contraction in the global job market. China’s job market is expected to shrink by more than 10 million this year. In order to cope with the difficulty of graduating students, the Chinese government has introduced multiple policies including expanding the recruitment of government’s civil servants. Unfortunately, these policies do not include Chinese students returning from overseas. In the meantime, Australia’s situation is also not so optimistic. The unemployment rate has reached 6.2% in April. About 600,000 people have left the workforce. The Australian government has introduced financial subsidies for the unemployed and those with reduced working hours. However, the protection from the government has not yet benefited international students.

Chinese oversea students have been forgotten by both sides.

“I was so anxious that I couldn’t sleep all night,” Hui said.

After Hui returned home from Thailand, she began to look for a job. She sneered: “This is the helpless move from the person who can not go to school.”

Unfortunately, by the time Hui returned from Thailand, she has already missed the spring recruitment in China. It was until June that she finally found an internship.

“You can’t imagine how hard it was to find a job! No one was hiring. It took me months of torture to find this job.

“The pandemic has completely disrupted my plans. I was supposed to graduate at the end of this year, and then go back to China to take part in the spring recruitment in the following March. Now I haven’t been to school for six months and just found the desired internship. I actually really don’t know what to do for the next semester. The school hasn’t informed us about the following plans yet. I don’t know if I can get back to Australia. If I can go back, Then I have to give up the internship. But if it’s the same as last term, Then I might have to defer it again,” Hui’s tone gradually wavered as she spoke.

“I have to keep paying my rent in Sydney, even though I’m not in Sydney. The current situation also makes me unsure whether I should renew the lease or not. The rent alone is a lot of money.”

Hui’s anxiety is real and urgent, but the students who were back in Australia are equally unhappy.

“I had two options, one was to graduate and get a job, and the other was to do a Ph.D. This year the job market has left me with no choice. The pressure of getting a job is so serious that I think I will choose to do a Ph.D.” Yanyun said.

“If I choose to do a Ph.D., it’s very likely for me to stay in the country where I do the Ph.D.”

“I was very careful not to go out in the past months. Staying at home has made me unable to gain strength from social connections. The quality of online classes was also low and they were hard to engage. The school’s councilors were useless in easing my pressure.” “She continued.

To governments and schools, Chinese oversea students should not be ignored

During this pandemic, these students from China might have become the most awkward ones, who have invested time and money just to be able to go to school, meanwhile bearing the pressure of not only social distancing, but also changing their life planning. Chinese students want to shout out to the governments and the universities to take reasonable actions to help them go through this hard time. Meanwhile, I hope this report can alleviate the pain and entanglements of Chinese overseas students because you are not alone and we are all fighting this dilemma together.

Be the first to comment