If you have been following recent Australian federal elections, you will notice that WeChat has never received more spotlight than this one.

As a matter of fact, many professionals and scholars have shared their perspectives on the rising importance of WeChat in Australian political campaigns. For example, Professor Sun published an article on The Conversation, titled “Chinese social media platform WeChat could be a key battleground in the federal election.”

Having worked in WeChat news production and marketing for almost 3 years, I am proud and concerned to see how much WeChat was taken seriously in this election.

This is a strange feeling.

It’s like seeing Brandon Stark taking the crown at the end of Game of Thrones. You know he has the ability to claim the winning title, but you just don’t know if he’s worthy.

I’m proud because a Chinese-language based social media platform can reportedly have such influential power in a foreign country.

But as an industry insider, I believe that this power is overrated.

There are advantages not to be neglected.

Yes, with 3 million monthly active users in Australia, WeChat is still winning the monopoly of targeting the Chinese community. There’s no denying it.

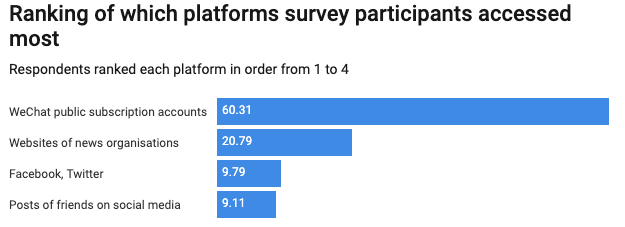

Chinese media researchers Haiqing Yu and Wanning Sun conducted a survey on the Mandarin-speaking community in Australia last year. They found out that 60.31% of them use WeChat subscription accounts as their main source of news and information.

In this federal election, several marginal seats with large numbers of Chinese-Australian voters were up for grabs. Therefore, both parties had intensified their presence on WeChat.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison opened a WeChat subscription accounts in February and started to make Chinese-language posts almost every day from the campaign trail and encourage people to vote for him.

As for the Labor party, there was a clear change in their strategies after they lost the WeChat battle in the last election. Besides from posting articles detailing his policies in Mandarin, Bill Shorten even participated in a WeChat live interaction session for the first time ever, fielding questions from 500 WeChat users.

How effective has it been?

It really depends on your definition of success.

Dr Joyce Nip, senior lecturer in the Department of Media and Communications in University of Sydney who has been researching the political and social implications of Chinese media in Australia, believed that both parties’ output was certainly valid.

“It’s always good to try and reach more people, but the result is quite unforeseeable sometimes,” she said, “WeChat is the most popular social media in the Chinese community after all.”

Both parties put themselves out there on the platform, but the outcome is whenever there was drama or misinformation circulating in WeChat subscription accounts, it’s always about the Labor party.

If we are simply looking at short-term result, the Liberal party did win this election.

But if we look at building relationship with the Chinese community in the long run, this is where the problems come in.

This is why WeChat is overrated as a campaign tool.

There are dozens of online Chinese-language media outlets operating in Australia. As mentioned above, their WeChat subscription accounts are the main source of news and information for the Chinese community.

Let’s do a little quiz to see how much you know about these accounts:

How do these WeChat subscription accounts generate news?

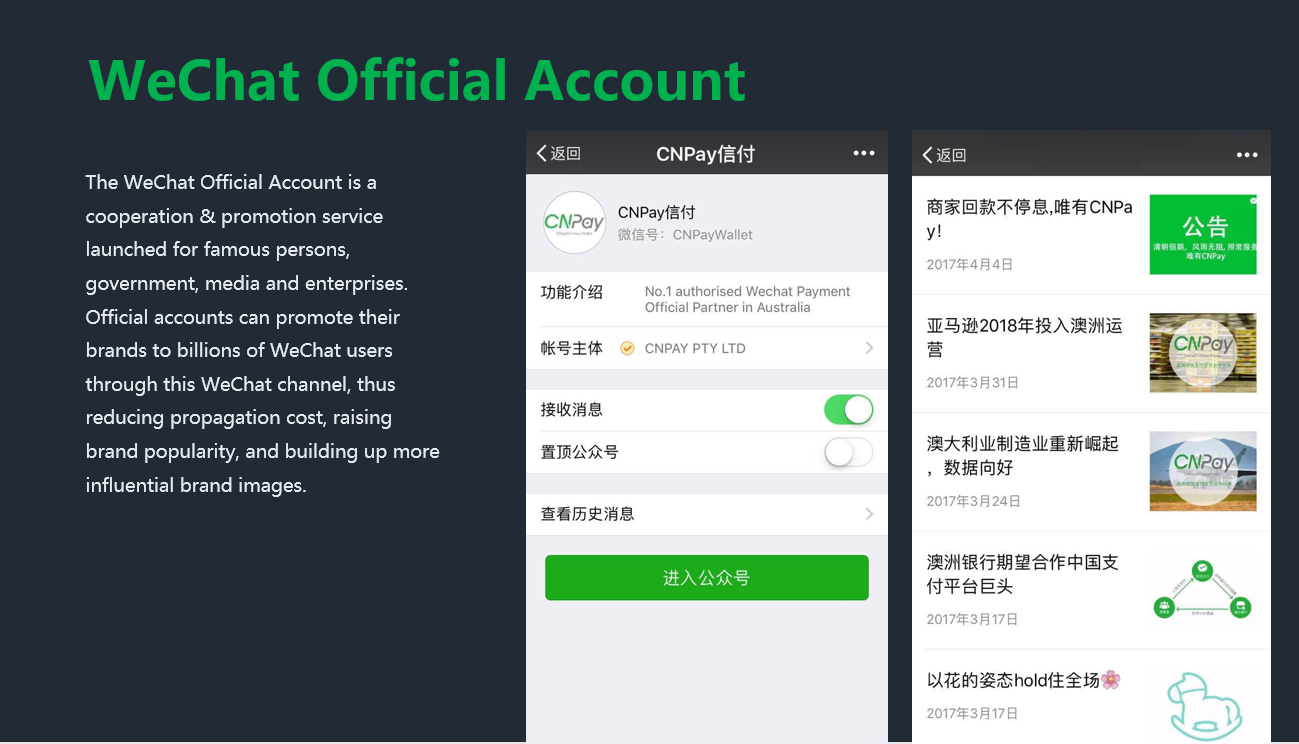

Source: Jetek China Digital

Source: Jetek China Digital

Editors from WeChat subscription accounts are performing what scholar Mark Deuze would describe as bricolage journalism. They translate, edit and synthesise published news articles from Australian and Chinese media outlets, through their own editorial lens.

These accounts are commercial entities and profit-driven, hence the No.1 goal of posting an article is to gain views.

The result is that the majority of these editors will post almost any information that will make a good clickbait for their audience, regardless of its credibility.

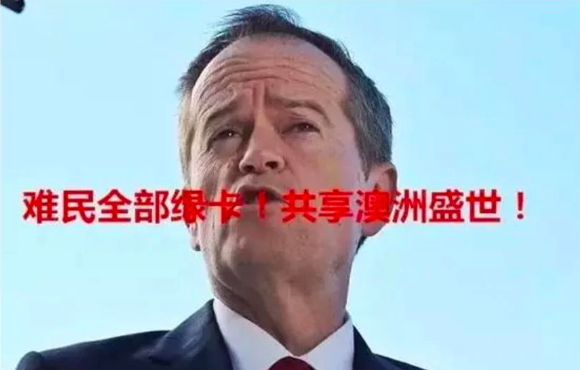

One of the most circulated fake news around WeChat subscription accounts is Labor’s “Green cards for all refugees”, do Chinese people actually believe it?

Source: Screenshot of a WeChat headline "Green cards for all refugees, share Australia’s prosperity!"

Source: Screenshot of a WeChat headline "Green cards for all refugees, share Australia’s prosperity!"

You will be surprised by how many Chinese people actually believe this and yelled at the Labor party when you look at the comment sections.

From my observation at work, Chinese-Australians, especially new immigrants from mainland China, susceptible to fake news due to their limited knowledge of Australian politics and current affairs.

“The information is easily disseminated. If something gets onto the social media, there’s no traditional gatekeepers there,” Dr Nip said, “Fake news can amplify or blow up without people filtering through whether it is accurate or not.”

The more concerning issue is that WeChat somehow falls into a grey area of regulations.

“The Chinese authorities may not be too concerned about what they do in Australia although WeChat belongs to a Chinese company,” she said.

“If it runs in Australia, I think it should also come under the jurisdiction of Australian regulation. But because WeChat is in Chinese language and it targets a small portion of the population, the main regulators may not be very aware of what is happening.”

If readers call out the misinformation in the comment section, or have questions about the article, will the editors respond?

Source: Screenshot of Labor's WeChat subscription account featuring an article 'Liberal should stop lying and apologize to the Chinese community'

Source: Screenshot of Labor's WeChat subscription account featuring an article 'Liberal should stop lying and apologize to the Chinese community'

According to Dr. Sun’s study on Chinese-language media companies in Australia and my experience, most of these news editors are students from mainland China and not many has had proper journalistic training. So they don’t feel responsible for clear the air.

Moreover, WeChat subscription account system allows editors to choose what comments they would like to display. And they usually prefer the most outrages and controversial comments because they attract more views.

“The people who run these WeChat accounts are opinion leaders because they choose what to put up there,” Dr Nip said.

I’m really not sure if these Chinese students are the most qualified to be opinion leaders for the Chinese community.

What are the ways you can evaluate a campaign that was run on WeChat subscription account?

Source: www.pymnts.com

Source: www.pymnts.com

Unfortunately, WeChat subscription account system cannot provide in-depth data analytics. It only allows PR practitioners to evaluate the campaign on a very basic level.

Dr. Nip also believed that it is not likely to sufficiently determine the effectiveness of WeChat campaign, “You would not be able to do it unless you talk to the people who follow the WeChat account and ask them if they believe it or not.”

So if any Chinese-language media company say they can provide you with a detailed evaluation report for your WeChat campaign, they are either unprofessional or just lying.

It takes more than WeChat.

Are these problems going to be fixed?

No, in a foreseeable future, no.

Should Australian politicians give up on WeChat?

No, I believe WeChat is still the most important method to achieve short-term informational goals. But if we are talking about building relationships with the Chinese community, politicians should not rely on a platform like this.

A strong relationship needs more than just a few articles on WeChat.

Not all Chinese-Australian voters use WeChat and for those that are on it, their opinions do not reflect nor represent the diversity of Chinese community. If you are serious about getting the vote from them, you should put in the extra effort.

You can start by talking to hundreds of Chinese-Australian community organisations across the country. A face-to-face communication can help you explore policy issues in greater detail and address Chinese-Australian voters’ needs at a deeper and more productive level.

And also, do it this weekend, not just before the election.

Be the first to comment